The Day the World Came to Ask the Forest for Permission

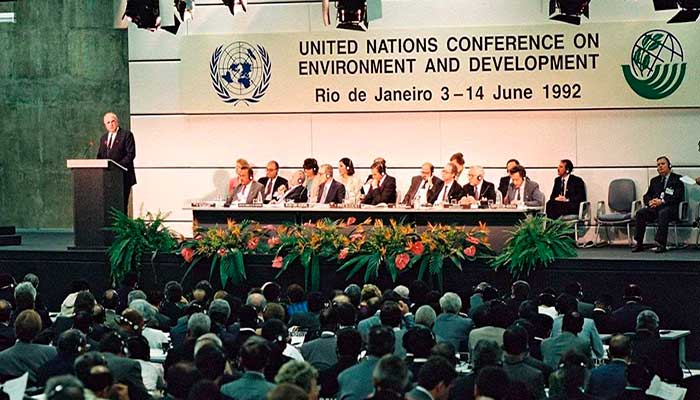

In June 1992, thousands of delegates, politicians, CEOs, journalists, and activists gathered in Rio de Janeiro for the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development—commonly known as the Earth Summit. It was one of the largest international meetings focused on sustainable development and environmental protection, a crossroads moment forcing humanity to confront the consequences of its actions on the planet.

But beneath the speeches, handshakes, and treaties, something far more profound—and far more unsettling—was unfolding.

The world had finally realized that the key to the future was hidden in the knowledge of those it had long dismissed as primitive: the Indigenous peoples of Earth’s last surviving rainforests.

As Jeremy Narby observed from the heart of Rio, the shock was palpable. Government leaders who once ignored or actively suppressed Indigenous populations were now invoking them in every treaty. Pharmaceutical and cosmetic companies were making pledges in front of cameras, speaking of “equitable access” and “shared benefit models.” Ethnobotanists were being treated like celebrities. Everyone, it seemed, had just discovered that Indigenous people had something modern science desperately needed.

But this was not a celebration.

It was an ambush.

The rainforest had become the final frontier of unexploited wealth. Its medicinal plants represented billions of dollars in untapped profit—yet the original guardians, the forest peoples, were once again at the risk of being erased.

The Amazon alone contains half of all plant species on Earth.

Less than 2% have been scientifically studied.

Of the plant-based medicines in modern hospitals, 74% were first discovered by Indigenous cultures.

Yet those cultures received almost nothing in return.

What the world was calling biodiversity—they called their ancestors.

The Awakening of the Industrial World

The biotechnology boom of the 1980s had opened a new gold rush. Scientists had unlocked DNA sequencing. Pharmaceutical labs were now able to isolate, extract, replicate, and patent active compounds from natural organisms.

Suddenly, every leaf, bark, and root in the Amazon wasn’t just a plant—it was intellectual property waiting to be claimed.

Western corporations had begun filing patents on Indigenous discoveries, converting tribal medicine into synthetic molecules, and then selling them back to the world at unimaginable markups.

The logic was simple:

- Indigenous people knew where healing plants were.

- Modern science could extract and patent those healing compounds.

- The rest of the world would never know the difference.

In Rio, this was not whispered. It was celebrated.

But then something unexpected happened.

The Indigenous people spoke.

They held their own summit in Kari-Oca—away from the cameras, away from the staged political theater. Delegates from the Amazon, the Andes, the Australian outback, the Arctic Circle, and African tribes gathered, not to beg the world for help—but to issue a warning.

Their position was unanimous:

The Convention on Biological Diversity, the centerpiece of the Earth Summit, was a trap.

It mentioned equitable benefit-sharing vaguely, but provided no legal mechanism to ensure Indigenous rights or prevent biopiracy. It was a document that recognized their knowledge, only to open the door to its systematic extraction.

They rejected it.

They called the unauthorized use of their plant knowledge a crime against humanity.

They demanded legal recognition of intellectual sovereignty over biodiversity and genetic resources.

Yet their voices did not make it to the main stage. Their truth was too inconvenient.

The industrial world had awakened to Indigenous knowledge—not as wisdom to be respected—but as a resource to be harvested.

And it had no intention of asking permission.

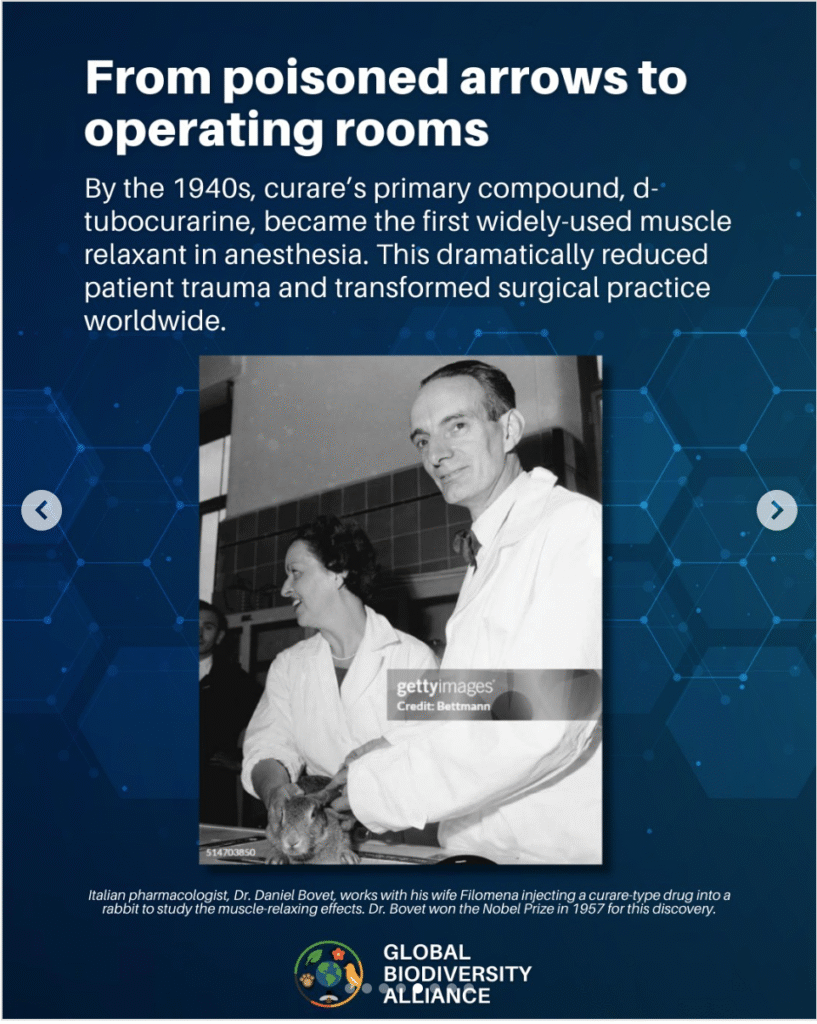

Curare – The Poison That Saved Millions (But Paid Its Creators Nothing)

One example dominated the discussions in Rio—a story that exposed the soul of this unfolding drama.

Curare.

For thousands of years, Indigenous Amazonians have prepared a muscle-paralyzing compound for hunting—what we now call curare. Their goal was precise: to kill game without spoiling the meat. Monkeys, for instance, when struck by an untreated arrow, would often wrap their tails around branches and hang out of reach, dying slowly while keeping the meat inaccessible. Hunters needed a method to stop the animals’ grip and make collection possible—without contaminating the flesh with poison.

The solution was curare: a complex mixture of over 70 plant species, carefully combined and boiled for up to 72 hours. Only some plants contained the active ingredients. The resulting paste paralyzes muscles without poisoning the meat, allowing the animal to fall gently to the forest floor.

The preparation was perilous. The fumes released during boiling were so toxic that a single breath could be fatal, and the final paste only worked when injected under the skin. Swallowing it had no effect, meaning its efficacy required precision beyond casual experimentation.

Western science long struggled to explain this ingenuity. How could forest dwellers, with no knowledge of hypodermic needles or molecular neurology, have discovered such a medicine by chance? It was a question science often refused to ask.

Yet the pharmaceutical industry had no such hesitation. From the 1940s onward, derivatives of curare—such as tubocurarine—became cornerstone drugs in modern surgery, enabling complete relaxation of the body’s muscles. This revolutionized anesthesia: surgeons could now operate on vital organs with precision, knowing that the patient’s muscles would not interfere, while the patient remained conscious under anesthesia or fully sedated with modern protocols.

Case Studies in Biopiracy: The Exploitation That Forced the World to Act

Curare was just one of many.

Case Study 1: The Neem Tree (India) – Ancestral Remedy

Used in India for over 2,000 years as antifungal, antibacterial, pesticide.

In 1994, the US Department of Agriculture and W.R. Grace & Co. patented neem-based extraction methods.

Indian farmers were suddenly required to pay royalties to use a tree their ancestors had worshipped.

The European Patent Office finally revoked the patent in 2000 after a massive legal fight led by Indian activists.

Source: European Patent Office Case EP0436257

Case Study 2: Turmeric (India) – Wound Healing

In 1995, the University of Mississippi Medical Center was granted a US patent for the use of turmeric powder in wound healing.

The Indian government provided Sanskrit texts from 500 BCE documenting the same use.

Patent overturned in 1997.

Source: USPTO Case 5401504

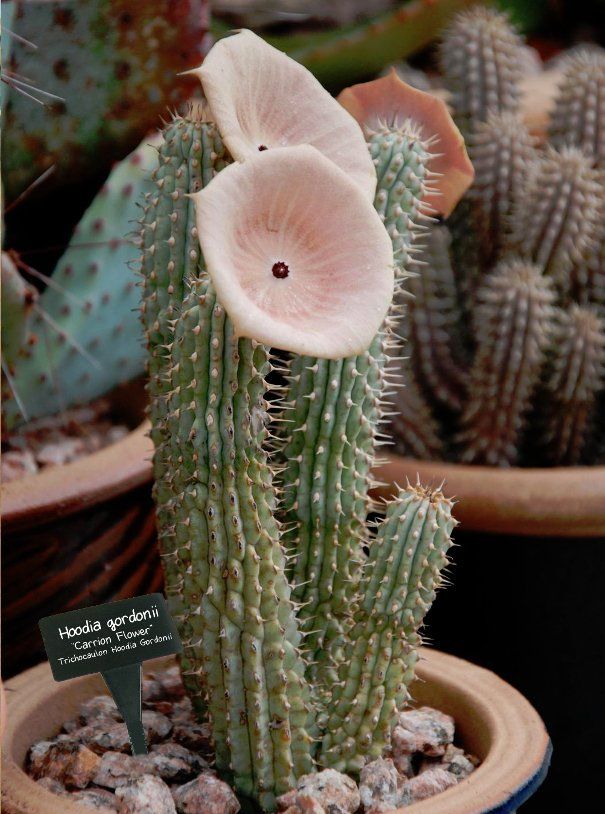

Case Study 3: Hoodia (Southern Africa) – Diet Pill

San people used Hoodia cactus to suppress appetite during long hunts.

Pharma company Phytopharm patented its active ingredient and licensed it to Pfizer.

San had not been informed.

Only after international exposure did they receive 0.003% of royalties.

Source: Nature, Vol 443, 2006

Case Study 4: Ayahuasca

In 1986, an American named Loren Miller patented the ayahuasca vine (Banisteriopsis caapi).

Patent was only revoked in 1999 after outrage.

Source: USPTO Patent #5751

Case Study 5: Cinchona Bark (South America) – Malaria Medicine

Quechua communities used cinchona bark for centuries to treat malaria.

European colonists extracted quinine and commercialized it globally.

The Quechua received no recognition or compensation for their centuries-old knowledge.

Source: Chavarria, L., Traditional Medicine and Modern Pharmaceuticals, 2008

Case Study 6: Quassia (Amazon) – Anti-Parasitic Research

Indigenous Amazonians used Quassia amara to treat fevers and digestive ailments.

Modern pharmacology later identified its antimalarial and anti-parasitic properties.

Indigenous communities were largely excluded from research benefits.

Source: Schultes, R., & Raffauf, R., The Healing Forest, 1990

Case Study 7: Periwinkle (Madagascar) – Cancer Drug Development

Malagasy healers used periwinkle for centuries to treat fevers and wounds.

Western researchers isolated its alkaloids, leading to the development of vincristine and vinblastine, chemotherapy drugs.

Indigenous knowledge was not acknowledged in the patenting process.

Source: Bakshi, B., Piracy of the Periwinkle: Extraction of Madagascar’s Traditional Indigenous Knowledge, 2025

Case Study 8: Amazonian Frog Secretion – Analgesic and Antibiotic Properties

Indigenous groups in the Amazon used frog secretions for pain relief and wound healing.

Western scientists identified antimicrobial peptides in the secretion.

Indigenous communities were not consulted or compensated for their traditional knowledge.

Source: Feres, R., Amazon Frog Highlights Appropriation of Indigenous Knowledge for Commercial Gain, 2022

In 2024, centuries after such exploitation, all 193 UN member states have signed a global treaty to prevent biopiracy. Companies seeking patents must now disclose and credit any Indigenous knowledge that inspired their inventions. This agreement marks a turning point: what was once taken from the Amazon and other ancestral lands without acknowledgment must now be recognized as living intellectual property belonging to its original custodians.

When Science Meets a Forbidden Truth

At the Earth Summit, there was one topic that remained unspoken—a truth so disruptive that even those who acknowledged it chose silence over ridicule.

The hallucinatory origin of Indigenous knowledge.

Throughout the Amazon, elders, healers, and shamans consistently claim that their botanical knowledge was not discovered through trial and error, nor by empirical experimentation.

They say they learned it directly from the plants themselves—through visions, dreams, and communication during ayahuasca ceremonies.

Western scientists, trained to believe that consciousness is an accidental byproduct of brain chemistry, deemed these claims “mythology.”

But what if they are not myths?

What if they are the operating system of a knowledge system far older, deeper, and more biologically integrated than science has ever imagined?

Ayahuasca – The Molecular Telephone Line

Ayahuasca is not a single plant. It is a precise biochemical synergy requiring at least two:

- Banisteriopsis caapi – a vine containing harmine and harmaline (monoamine oxidase inhibitors)

- Psychotria viridis – a leaf containing DMT (dimethyltryptamine), the most powerful known psychedelic molecule

Taken alone, neither plant produces a psychedelic effect. DMT is destroyed in the stomach. But when combined with the vine’s MAO inhibitors, the DMT becomes orally active, allowing it to reach the brain and induce visions.

This is not random. This is molecular engineering at a level that should be scientifically impossible without laboratory equipment.

- The Amazon contains 80,000+ plant species.

- Only a fraction contain DMT.

- Only a handful contain MAO inhibitors.

- Indigenous people not only discovered the correct combination but use dozens of admixtures in specific ratios to produce different visionary effects.

When asked how they figured this out, their answer is always the same:

“The plants told us.”

Modern science is now being forced to admit the plants may actually be communicating.

- In 2019, a study published in Frontiers in Psychology documented reports of consistent molecular insights gained by subjects during ayahuasca experiences, including chemical information about DNA and cellular structure.

- Researchers at Imperial College London are currently studying DMT’s interaction with human neurons and have found it increases neuroplasticity and promotes neuronal growth (Frontiers in Neuroscience, 2021).

This suggests that these visions may not be mere hallucinations—they could be transmissions of real information from the plant world.

As explored in ZenFusion’s previous blog series, The Silent Intelligence of Plants, based on Peter Tompkins and Christopher Bird’s The Secret Life of Plants, plants are capable of feeling, thinking, and communicating far more than we ever imagined. Perhaps Indigenous shamans, through their visionary practices, were tapping into this hidden intelligence all along.

DNA – The Cosmic Serpent Comes Into Focus

When Jeremy Narby first heard Indigenous shamans describing glowing serpents that communicate knowledge, he dismissed it as symbolic.

Until he started interviewing shamans across different tribes—and cultures thousands of miles apart, who had never met—only to hear the same description, repeatedly:

Two intertwined serpents of light.

The source of life itself.

They speak in geometries, in songs, in languages of vibration.

He was stunned.

Why?

Because that is precisely the structure of DNA—the double helix, the basis of all biological life.

Shamans, with no formal education, were describing DNA-like imagery thousands of years before modern science discovered it.

Is it possible that ayahuasca allows consciousness to perceive the molecular basis of life directly?

Western science says no.

Modern research is beginning to say… maybe.

- Dr. Michael Winkelman (Arizona State University) argues that shamanic states access “non-local consciousness” allowing interaction with biological information fields (Journal of Psychedelic Studies, 2021).

- New experiments show plants use electrical signaling networks similar to neural systems (Trends in Plant Science, 2020).

- DNA itself emits biophotons—tiny packets of light—which could form a communication network within and between organisms (International Journal of Quantum Chemistry, 2022).

The Ultimate Blind Spot of Western Knowledge

Narby recognized the paradox at the heart of modern civilization:

Indigenous knowledge produces results that Western science uses and profits from.

But the method of obtaining that knowledge—hallucinatory communication with plants—is dismissed as superstition or psychosis.

Meaning:

- Science accepts the products of Indigenous knowledge.

- But it rejects the process that created it.

This is Western hypocrisy in its purest form.

Two fundamental dogmas prevent science from accepting Indigenous claims:

- Hallucinations cannot be sources of true information.

- Plants do not possess intelligence or the ability to communicate.

If either of those statements is proven wrong—even slightly—it would shatter the foundation of modern science.

Yet the evidence is mounting.

The Living Internet of the Forest

Recent research has shown that forests are not random clusters of trees competing for survival. They form vast communication networks.

- Mycorrhizal fungi connect tree roots, forming a network that scientists now call the “Wood Wide Web”.

- Trees send electrical signals warning of predators.

- They exchange nutrients with genetically unrelated neighbors.

- They use airborne chemicals to warn nearby plants of insect attacks.

This is communication.

This is community.

This is intelligence.

Source: Suzanne Simard, Nature, 1997; Merlin Sheldrake, Entangled Life, 2020.

If plants and fungi transmit biochemical messages to each other… why is it so hard to believe they can transmit messages to us?

Indigenous people have always known that the forest is not silent. It is speaking. We simply never learned how to listen.

ZenFusion’s reflection

We cannot truly learn when our glass is already full. Yet why do we struggle so fiercely to listen, to observe, to accept ways of living that differ from our own? Why do we cling so stubbornly to the belief that only what we do, think, or feel is right—while dismissing centuries of wisdom held by others? What gives us the arrogance to reject ways of living that our ancestors relied upon for survival, for balance, for harmony—simply because they don’t fit into the neat pages of textbooks that grant us qualifications, status, and power?

Jeremy Narby’s time with the Ashaninka offers a piercing insight. When the tribals asked him how he made his tools, he realized a truth that modern society rarely admits: our systems have trained us to be “good enough” to keep the machinery running—but how grounded, how human, are we really? If even a fraction of us were truly connected to the world around us, we would not exploit or destroy it in the name of progress. Empathy is dismissed as weakness. Narcissism is rewarded. Self-indulgence is celebrated. Acts of love are viewed with suspicion.

From global politics to family hierarchies, from corporate boardrooms to intimate relationships, the drive for dominance, the thirst for selfish gain, and the normalization of corruption silently govern human behavior. These patterns—of control, of greed, of disconnection—are the hidden architects of our suffering, our stagnation, and our alienation—from each other, from ourselves, and from the living world.

In his film, ‘Triangle of Sadness‘, Ruben Östlund reveals the absurdity of human obsession with power and status, reflecting the very psychological patterns that disconnect us from empathy, humility, and connection.

It is no wonder that in a society shaped by screens, exams, and rigid definitions of “success,” alternative ways of knowing feel alien, even threatening. To truly learn is to become a student of life: to unlearn, to relearn, to let go of what we cling to and make space for what we have never seen. This requires patience, reflection, and courage—the very qualities our hurried, stress-driven lives often deny us.

Consider modern medicine. Many professionals, like Narby with his media tools, rely entirely on what they know, unaware of the deep roots from which that knowledge springs. And yet, they may dismiss traditional medicines—even in cases where centuries-old remedies succeed where modern methods fail. Perhaps defending what we know so fiercely is simply a reflection of the time, effort, and sacrifice invested in it.

Now imagine a different world. A world where we move beyond “I am right, you are wrong” toward humility, curiosity, and collaboration. A world where humans seek connection instead of dominance, where harming a part of the Earth is understood as harming ourselves. If we approached life hand in hand, with each other and with nature, the planet itself could heal. It is time to shift from “me” to “us.” Relationships—between people, and between humanity and the Earth—can only flourish when shared well-being outweighs ego. In embracing our interconnection, we open the door to true harmony, peace, and love.

Perhaps the forest, the shamans, and the stars are whispering the same truth: wisdom asks us to empty our hands, our minds, our hearts. To listen without judgment, to learn without ego, to recognize that the world is not ours to conquer, but ours to care for. The knowledge of the ages—encoded in rivers, plants, and Indigenous ways of life—awaits those willing to approach with humility, reverence, and openness. Only when we step beyond the illusions of control, the pride of certainty, and the fear of the unknown can we glimpse the harmony that has always been there. In embracing this, we may heal not just the Earth, but ourselves—and discover that connection, wonder, and love are the true legacies worth passing on.

If you’re eager to explore further, the following books—all available on Amazon India—have been carefully curated to expand your understanding of Amazonian plant wisdom, biopiracy, ancestral science, and the ongoing struggle between Indigenous traditions and modern pharmaceutical power. Click on the books that interest you to place your order.

Books

The Fellowship of the River: A Medical Doctor’s Exploration into Traditional Amazonian Plant Medicine by Gabor Maté MD, Joseph Tafur MD

This book reveals why modern medicine struggles with emotional and psychosomatic illnesses like depression, PTSD, and chronic pain—conditions deeply rooted in the emotional and spiritual body. Through his experiences with Amazonian plant medicine, Dr. Tafur shows how ayahuasca and traditional healing practices open pathways between mind, heart, and body, presenting a powerful new paradigm for true holistic healing.

Wizard of the Upper Amazon: The Story of Manuel Córdova‑Ríos by Cordova-Rice Lamb

This book tells the remarkable life of Manuel Córdova-Ríos, a mestizo who was taken in by an Amazonian tribe (the Huni Kui) and trained in their herbal and visionary practices.

The Healing Power of Rainforest Herbs: A Guide to Understanding and Using Herbal Medicinals by Leslie Taylor

This book presents more than seventy rainforest plants and how traditional cultures use them medicinally. Bridges Indigenous use to modern pharmacology.

Biopiracy: The Plunder of Nature and Knowledge by by Vandana Shiva

A foundational critique by Vandana Shiva exploring how Western corporations have commodified traditional knowledge and natural resources.

Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer

This book explores Indigenous ecological knowledge alongside Western science, weaving together stories of plants, ethics, and communication.

Global Biopiracy: Patents, Plants, and Indigenous Knowledge by Ikechi Mgbeoji

This book sheds light on how global patent frameworks enable the transformation of Indigenous knowledge into Western “invention.”

Biopiracy in the Amazon: A Legal‑Political Approach by Ligia Lopes

Focuses specifically on the Amazon region and details how biopiracy takes place in that biodiverse context—legal loopholes, Indigenous rights, policy failures, and the commercial exploitation of forest resources.

Biopiracy Of Biodiversity: Global Exchange as Enclosure by Andrew Mushita, Carol B. Thompson

A collection of essays on how biodiversity—especially from the Global South—is enclosed and commodified under global intellectual property regimes.

Confronting Biopiracy: Challenges, Cases and International Debates by Daniel Robinson

This book explores many case-studies, legal battles and global treaties related to biopiracy.

Native Science: Natural Laws of Interdependence by Gregory Cajete

This book addresses Indigenous ways of knowing, relationships with nature, and how Western science has often dismissed these systems.

Advances in Natural Product science provides the summarized information related to global herbal drug market and its regulations, ethnopharmacology of traditional crude drugs, isolation of phytopharmaceuticals, phytochemistry, standardization and quality assessment of the crude drugs.

Medicinal Plants and Traditional Knowledge in the Indian Subcontinent by Dr. DEBABRATA DAS EDITOR

This book bridges the global south context and shows how traditional knowledge in one region functions.

References

- Chavarria, L. (2008). Traditional Medicine and Modern Pharmaceuticals.

- Schultes, R., & Raffauf, R. (1990). The Healing Forest: Medicinal and Toxic Plants of the Northwest Amazonia.

- Bakshi, B. (2025). Piracy of the Periwinkle: Extraction of Madagascar’s Traditional Indigenous Knowledge.

- Feres, R. (2022). Amazon Frog Highlights Appropriation of Indigenous Knowledge for Commercial Gain.

- Dharmananda, S. (2007). Yunnan Baiyao: From Traditional Medicine to Global Brand.

- Acharya, D. (2008). Bhumka: Guardians of Traditional Herbal Knowledge in Patalkot Valley.

- Nature. Vol 443. (2006). Hoodia Appetite Suppressant Patent Controversy.

- European Patent Office Case EP0436257. Neem Tree Patent Revocation.

- USPTO Case 5401504. Turmeric Wound Healing Patent.

- USPTO Patent #5751. Ayahuasca Vine Patent Revocation.

- Frontiers in Psychology. (2019). Ayahuasca and Molecular Insights.

- Frontiers in Neuroscience. (2021). DMT Interaction with Human Neurons and Neuroplasticity.

- Suzanne Simard. (1997). Nature. The Wood Wide Web: Mycorrhizal Fungi Networks.

- Merlin Sheldrake. (2020). Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds & Shape Our Futures.

- International Journal of Quantum Chemistry. (2022). Biophoton Emission by DNA and Cellular Communication.

- Jeremy Narby. (1998). The Cosmic Serpent: DNA and the Origins of Knowledge.

- Peter Tompkins & Christopher Bird. (1973). The Secret Life of Plants.

- Vandana Shiva. (1997). Biopiracy: The Plunder of Nature and Knowledge.

2 Responses

A very deep overview of the current scenario. Something everyone should be aware of. Nice work.

Thank you — truly.

It’s one of those topics that sits quietly in the background of our lives, but affects far more than we realise.

The more people become aware of what’s happening, the harder it becomes for these things to slip by unnoticed. Grateful you took the time to read and reflect on it.